By James Barron

Dec. 3, 2024

What is a landmark? What should a landmark be?

Those questions have come up in different ways in the last few days, first in an essay by The Times’s architecture critic, Michael Kimmelman, then in an annual list by the Cultural Landscape Foundation, an education and advocacy organization.

The list is a departure for the group. In the past it has zeroed in on “at-risk landscapes.” This time there’s a beach in Miami, a levee in Louisiana — and, in New York City, a park and a playground in another park. Not one of them is deteriorating or facing demolition. They made the list because they are places where protests unfolded — protests that the foundation says are in danger of being forgotten.

The sites have “a unique power of place because they serve as reminders that they were the stages for those events where it happened,” said Charles Birnbaum, the president and chief executive of the foundation, adapting a line from the song “The Room Where It Happens” in the musical “Hamilton.” The foundation said that protests and civil disobedience at the sites on the list were “not only a defining part of our shared history since the colonial era, but they also continue to the present day on campuses, at political conventions and elsewhere.”

The two sites in New York City were chosen because 2024 is the 50th anniversary of the publication of Robert A. Caro’s classic, “The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York.” Both fit the foundation’s theme because in both places protesters mobilized — and the seemingly all-powerful Moses did not get his way.

One is Washington Square Park, where Moses wanted to build a roadway that would have forever changed “the relationship between the public space and its value as a common green,” the foundation said.

Over 23 years, Moses put forward three road plans, the foundation said, and community members stopped them “in a grass-roots movement that inspired historic preservation efforts throughout the city.” This was long before the demolition of the old Pennsylvania Station in the 1960s, an event that prompted the passage of preservation laws and the creation of the Landmarks Preservation Commission to prevent beloved buildings from being torn down at will.

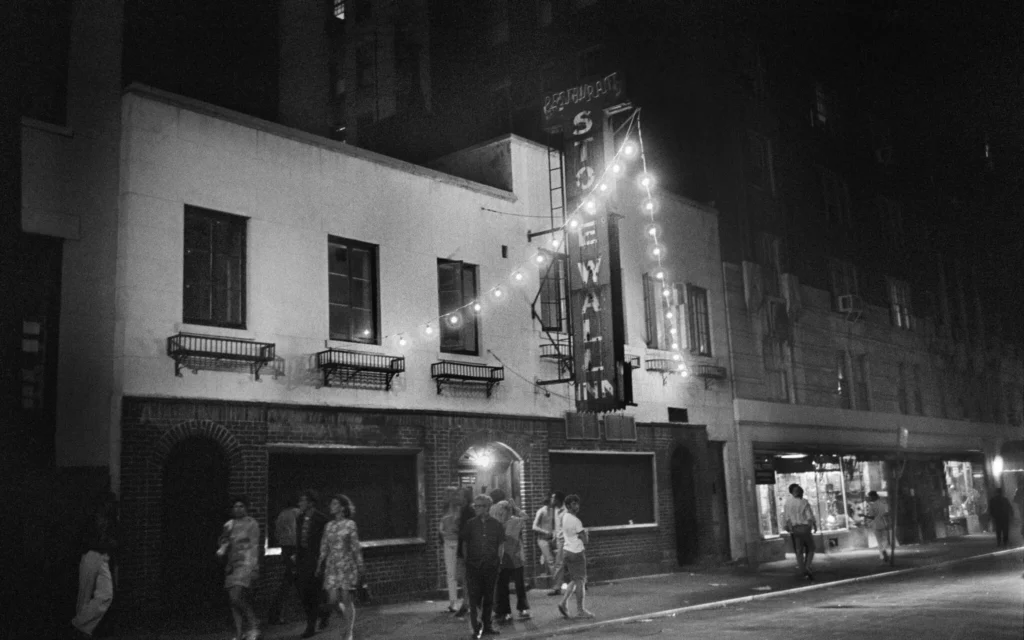

The other New York site on the list is the West 67th Street Playground in Central Park, which Moses wanted to turn into an 80-car parking lot for the Tavern on the Green restaurant.

Mothers from the neighborhood “occupied the site along with their children and dogs” in 1956, the foundation said. “They set up chairs and refused to leave,” the foundation continued. Moses ordered trees to be taken down but relented after newspapers called the protest “the Battle of Central Park.” He eventually abandoned the parking lot plan; the site is now known as the Tarr-Coyne Tots Playground.

“ ‘The Battle for Central Park’ represented a turning point in children’s recreation as the mothers successfully made their case for prioritizing children’s play areas over parking infrastructure,” the foundation said. That fight, in turn, led to further advocacy “on behalf of the city’s children and the appropriate use of public parkland,” it said.

The foundation’s list seemed to dovetail with what Michael wrote about landmark laws: They “don’t always protect what we actually want to save.” His essay was adapted from a chapter in “Beyond Architecture: The New New York,” edited by Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, to be published next week by New York Review Books.

Often there’s a disconnect between buildings that appeal to government officials and preservationists and the more neighborhood-oriented places that appeal to locals — the bodega or bookstore on the corner, or a farmers’ market. As he put it: “How do we treat less obvious or tangible things and values like the physical fabric of a community or a sense of place?”

A city’s intangible heritage “need not be a building or place,” he wrote, before noting that “intangible heritage is the next frontier for preservation in America.”

“In the end,” he wrote, the questions surrounding intangible heritage “come down to how we wish to define and enshrine our neighborhoods, our culture and ourselves.” And the discussion “is a crucial part of the preservation process.”

What are the standards for a place to be considered for landmark status? Tell us your thoughts!